Five and a half minutes is about how long it takes to microwave a pot pie or listen to Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” once through. It’s also how long the intense shaking from the Cascadia Earthquake — often referred to simply as “The Big One” — is expected to last.

Nearly nine years ago, a magnitude 9 earthquake shook the northeastern corner of Japan for close to six full minutes. The March 11, 2011, earthquake with an epicenter near Tohoku destroyed more than 120,000 buildings and, according to Japan’s Reconstruction Agency, caused an estimated $199 billion dollars of damage, making it the most expensive natural disaster in world history.

Experts say a similar earthquake is “overdue” and should be expected to hit the Pacific Northwest within the next century, if not sooner.

Researchers from regional universities, geotechnical engineers and emergency response agencies expect the earthquake to wreak havoc when it hits, bringing about the collapse of roads and bridges and rendering electricity and water infrastructure useless.

While some effects from natural disasters are unavoidable, experts are growing increasingly concerned about the lack of preparation by both governing bodies and individuals.

A ticking subduction zone

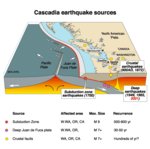

The Pacific Northwest sits on the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which stretches from the north end of Vancouver Island in British Columbia to Cape Mendocino, California, a distance of 620 miles. Cascadia is the meeting point of the smaller Juan de Fuca plate and the large North American plate. As the two tectonic plates converge, one is forced under the other.

This causes the oceanic crust of the Pacific Ocean to move under the continent of North America at a rate of about 40 millimeters (1 ½ inches) per year.

The 2011 earthquake in Japan was due to this same type of fault line.

Alison Pyrch, an associate geotechnical engineer at Hart Crowser, explained that the deeper an earthquake is, the longer it causes shaking at the surface. The creates a much higher potential for damage. A 30-second earthquake usually reaches a 7 or higher on the Richter scale, while a two-minute quake reaches an 8 or higher. By four minutes, an earthquake is at 9.0.

Along with depth, seismologists use the size of crustal breaks to indicate how powerful an earthquake could be. The 1989 Loma Prieta, California, earthquake had a magnitude of 6.9, enough to cause more than $6 billion in damage and kill 63 people. Loma Prieta sits on one of the most well-known and studied fault lines in the United States, the San Andreas Fault. According to the United States Geological Survey, the San Andreas Fault is capable of producing an earthquake no larger than a magnitude 8.3 due to its close proximity to both the surface (10 to 12 miles deep) and the size of crust that can break during an earthquake on the San Andres.

More than 40 miles below the earth’s crust, the Juan de Fuca plate is moving under North America and melting into the earth. However, around 30 miles down, the North American plate is stuck, causing pressure to build up underneath the surface of the earth. As the Juan de Fuca plate continues to move, the North American plate gets put under more pressure. Eventually, the pressure will become too much and the North American plate will snap upward, much like a breaking rubber band. Since the Cascadia Subduction Zone sits anywhere from 7 to 18 miles deeper than the San Andreas, if the entire plate breaks off, an earthquake larger than a 9.0 is more than likely.

“Geology works on a really long time scale, and we’ve been around for an eyelash of that really long time scale,” Pyrch said at “Science on Tap,” a seminar on earthquakes at Kiggins Theatre last month.

Pyrch explained how due to this larger-than-life timescale developing exact data on where and when an earthquake will happen is not possible.

Pyrch said the only way to make a prediction is to look at history. On average, a rupture in the Cascadia Subduction Zone happens once every 243 years, putting it around 75 years overdue. A large scale earthquake hasn’t happened since January 26, 1700, 76 years before the Declaration of Independence was signed.

Seismologists and geologists are able to determine these estimates by looking at the limestone of the seafloor and comparing it with the highly documented tsunami records of Japan. Before 1700, there was about a 780-year gap between the Cascadia earthquakes (920 to January 26, 1700).

According to an Oregon State University research team led by marine biologist Chris Goldfinger, throughout the past 10,000 years there have been at least 41 earthquakes on the Cascadia Fault Zone with 19 being a “full margin rupture” where the entire zone snaps.

Goldfinger said there’s a 33% chance of this “megaquake” hitting the Pacific Northwest in the next 50 years.

“Perhaps more striking than the probability numbers is that we can now say that we have already gone longer without an earthquake than 75% of the known times between earthquakes in the last 10,000 years,” Goldfinger said in a statement earlier this summer. “And 50 years from now, that number will rise to 85 percent.”

What a quake will look like

Pyrch says the Pacific Northwest is not at all prepared for an earthquake of this magnitude. She rates cities such as Portland at a 2.5 to 3 on a scale of 10 in terms of preparedness.

“Our biggest lack is public education and public preparedness,” she said.

Pyrch says populations around the world that are accustomed to a lack of electricity and water are significantly more prepared for a disaster such as an earthquake.

Pyrch offered Mexico and Japan as examples of countries well prepared in 2019. Both countries have earthquake early warning systems and a large culture built around the idea that a quake could hit at any moment.

“If people are prepared for an event and they know it’s going to happen and they are educated, they are significantly better when it comes to handling an event,” she said. “As it is, we are not prepared simply because our society will not be bouncing back as quickly because we depend on all those utilities.”

Pyrch’s second problem with preparedness in the region is infrastructure. If the “Big One” were to hit this year, she believes most of the transportation hubs — land, sea and air — would all be compromised. Along with this, she mentioned that there will be significant landslide damage as well as the explosion of natural gas and liquid fuel lines and ruptured water pipes.

Liquid fuel in Southwest Washington is refined in the Seattle-Tacoma area and is transported through a pipeline that is “not seismically sound,” Pyrch said. She added that fuel for the area is stored near the Willamette River where there is an expected movement of 25 feet. The spread of fire is also a major concern given that many of the water lines will likely break, Pyrch said.

Pyrch noted how most of the electricity in the area is supplied by the Bonneville Power Administration. If its power and energy network falls due to an earthquake, power in the area is expected to go out for an indefinite period of time.

“We are spoiled and we expect everything to work on demand,” she said. “Our society does not function without running water, electricity and our cellphones and communication networks working.”

In her seminar, Pyrch said soils in the Pacific Northwest are subject to liquefaction, the process of soils with a large water content losing strength due to a strongly applied force such as an earthquake. Under this force, sand and mud sink into the ground causing the buildings and structures on top of them to follow. Pyrch said soil underneath large economic hubs such as the Interstate 5 Bridge, the Glenn Jackson Bridge and the Portland International Airport all sit on liquefiable soil.

Pyrch expanded on liquefaction damage in a followup interview, explaining that the I-5 Bridge is “pretty much toast” if a large earthquake were to hit, but the bridge across I-205 might be salvageable.

“From what I understand there is a chance that it will be repairable,” Pyrch said about I-205, adding that while it might be repairable, it will not be a structure people are going to be able to drive over immediately.

The destruction of these bridges and economic trade hubs such as the Port of Portland and Portland International Airport (PDX) is expected to dramatically impact the surrounding area’s economy.

“One of the points of the (2011) Japan earthquake was that their economy took a big hit. In fact, the world economy took a big hit,” Pyrch said while explaining that one of the reasons the area needs to get ready for an earthquake is the fact that not everybody is going to die in the initial shock of the quake. Most people will survive, and building infrastructure for that survival period is key to withstanding the earthquake, she said.

Preparing

Timothy “T.J.” Miller, of Battle Ground, has a degree in power systems and works for BPA. He echoed Pyrch’s statements while pointing to the solar panels and generators he has installed in his earthquake-proof shop.

“The irony of it is that I work for the power grid and yet I have solar and a generator because I know the grid is going down,” he said.

Miller has spent nearly his whole life preparing for disaster to strike.

“I don’t really know what made me want to be a survivalist other than the fact that I have five sisters and my mom always said, ‘you’re the man of the house, you’re going to have to protect your sisters,’” he said. “I grew up in fear that I wouldn’t be able to protect (them). It’s an overcompensated thing about me and I can’t help it.”

Miller built a shop on his property for his business, Silenced Weapons. The shop doubles as his survival shelter, and he said it is structurally sound and can withstand an earthquake.

“This shop is built better than any of the houses around here,” he said. “The inspector said if we were to have the subduction zone earthquake, all the houses (nearby) would be gone and this shop would still be here.”

Miller believes a lack of food, water and shelter will be the biggest problems facing citizens in the Clark County area if disaster were to strike. He suggests bolting down everything in houses and shops and having enough food and water to sustain yourself and dependents.

“Water, water, water,” Miller said when asked about what he feels is the most important thing people can do to prepare.

Miller’s shop is equipped with a two-year supply of food and water for him and his wife. Some of his equipment includes a sun oven, more than 10,000 gallons of fresh water and a system to brew his own beer.

“Some people say it’s not a key part of preparedness, but I think it is,” Miller said as he opened a door in the back of his shop revealing a home brewery where he makes India Pale Ale.

Also in Miller’s shop is an old ambulance from the Los Angeles Police Department that he is renovating to be a disaster vehicle complete with a few days worth of food, a fire ax and a truck vault, something he builds to securely store items in a vehicle. Also equipped with a truck vault is Miller’s Jeep Wrangler, which has everything from a snorkeling system to an air compressor.

“It’s got everything I think people should have on their car in case of a disaster,” Miller said before pulling out the truck vault containing a flare gun, hiking equipment and enough food and water to survive for a week. Miller said a lot of the ideas for his Jeep came after he experienced the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and realized how unprepared people in the area were.

“The only thing that made it out of the city were the 4-by-4’s,” Miller said.

While Miller and his wife may be prepared if the Cascadia Subduction Earthquake were to strike, a good majority of the Clark County and the Portland Metro Area has not started preparing. Pyrch believes this lack of preparedness can be changed by working together to build an “earthquake culture.”

While Miller may have a two-year supply of food, Savannah Brehmer of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommends having a minimum of 72 hours, but encourages a supply of up to two weeks of food, water and necessary medicine.

“We also recommend people know their community because if you know them in advance, it’s going to help out in terms of sharing resources,” Brehmer said. “Resources may be spread thin in the event of an earthquake.”

FEMA’s website outlines a three-step plan citizens should have to prepare themselves for disaster. First, protect yourself before an earthquake. To do this, FEMA recommends practicing what to do during in an earthquake, gathering critical documents and building a preparedness kit that lasts at least three days. Second, protect yourself during an earthquake and drop, cover and hold on. Lastly, protect yourself after an earthquake by monitoring local news reports, exiting damaged buildings and staying away from damaged areas. If your home has been damaged after a disaster or is no longer safe and you need a place to stay, text SHELTER and your ZIP code to 43362 to find the nearest public shelter in the area.

Pyrch recommends doing everything possible to secure your home, such as strapping it to the foundation and knowing how to turn off the gas and water lines leading to your home. “Make sure your home is safe and somewhere you can be for two to four weeks without help,” Pyrch said. Along with this, he recommends building emergency lists and getting what you need whenever you’re at the grocery store.

“If you have an extra five bucks, get that extra gallon of water,” she said.

Eric Frank, the Public Information Officer of the Clark Regional Emergency Services Agency (CRESA), recommends doing all of the above and repeating it for your workplace and your vehicle, mentioning how not everyone will be at home when disaster strikes.

“I want to make sure I have whatever I need no matter where I am when disaster strikes,” he said. “Those are the messages we spread constantly.”

Building an ‘Earthquake Culture’

During “Science on Tap” and in subsequent interviews, Pyrch stressed the importance of building a culture around preparedness for earthquakes. This culture, dubbed “earthquake culture,” revolves around education about earthquakes and the substantial followup damage they will cause.

“Educate yourself and your neighbors because until we are educated about the problem, we

are not going to make any progress,” Pyrch said. “Until it is a priority within our society and in our communities to be ready to handle a large earthquake, we are not going to be ready.”

To discuss this “earthquake culture” Pyrch uses the example of other countries such as Japan and Mexico around the Pacific Ring of Fire that she believes are prepared if disaster were to strike tomorrow. She mentioned activities such occasional statewide earthquake drills.

“They can evacuate a building in under two minutes,” Pyrch explained.

She later used the example of a fire drill at a public high school to show how unprepared the United States is in terms of a disaster.

“Do adults make it out in two minutes?” she asked.

Pyrch pressed the need for educating yourself, your family and your neighbors about the importance of preparing for an earthquake, something CRESA believes to be just as important as building your own personal disaster kit.

“Having the mindset (for disaster) is the biggest piece,” Frank said. “A positive attitude and connecting with your neighbors ... are what is going to make our communities stronger and more disaster-resilient.”

Frank noted that images from recent disasters show neighbors helping neighbors, not first responders in uniform. Frank said connecting with neighbors before a disaster is important because the area as we know it will end up with fractured roads and downed bridges, making it harder for first responders to reach disaster sites.

“It’s going to be neighbors relying on each other for the first few hours and days of a disaster until we (emergency response) can make that connection again,” Frank said.

CRESA Emergency Management Division Manager Scott Johnson said, in the past, the government had hard-set plans for if disaster were to strike.

“From about 1945 up until 2005, there was an idea that governments should have very detailed plans that covered every aspect of every potential thing that could go wrong,” Johnson said. “We had a very, very detailed earthquake plan and a very, very detailed flood plan.”

Now, Johnson said governments and emergency response agencies have changed their mindset from hard fixed plans to the concept of “planning” because putting emergency plans in hardset “silos” can cause confusion about which plan to use during a disaster.

“Planning is a concept that revolves around looking at what is actually going on and the impact it has on people’s life safety, the severity of the incident and the impact to our key infrastructure,” Johnson said. “Our plans have gotten much more flexible. Our plans have gotten much more responsive. That allows us to deal with things more effectively but it also means that we need a more informed and engaged citizenry because we need you (citizens) to buy us time to assess what is going on.”

Johnson and Frank recommend taking classes, building a community with neighbors and reminding elected officials to prepare for disaster before it strikes.

“It takes educated community members to remind our elected officials all the time that this is an important topic,” Frank said.

Brehmer repeated CRESA’s thoughts about becoming more educated and even suggested talking to Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) in the area. The CERT program educates volunteers about disaster preparedness for hazards that might impact the area, such as earthquakes. The CERT program also trains volunteers in basic disaster response skills, such as fire safety, light search and rescue, team organization and disaster medical operations.

Amanda Siok, the earthquake contact for FEMA Region X (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon and Washington), also highlighted the importance of individually preparing and gaining these skills and the impact they have on the community.

“It is really important that the public prepares themselves because the less prepared individuals are, the less prepared the community as a whole will be,” Siok concluded.